This is where I live, and this is one of my favourite mornings.

Category Archives: News

Audiobooks

I love listening to audiobooks. Now you can listen to The Ill-Made Mute as an audiobook, and hear the pronunciation of all those outlandish words and names you wondered about.

The Lady of the Sorrows audiobook is now available on Kobo and will soon be everywhere else.

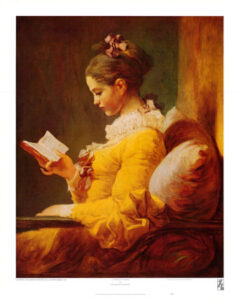

The hands that wrote the Bitterbynde Trilogy

Cecilia writes in a notebook.

The voice of CDT

Cecilia reads a poem from ‘The Ill-Made Mute’.

The first page of The Ill-Made Mute

Here’s another short video . . . .

Inspirations for “The Churchyard Yarrow” & “Madigan’s Leap”

The inspiration for writing Madigan’s Leap in the first place was British and Irish folk music. I have always loved the lyrics and melodies of folk songs, and grew up listening to the music of, amongst others, Steeleye Span and Fairport Convention. The fascinating—and to me, unusual—lyrics of many of these songs taught me much about history.

In particular I found the horrific stories of press gangs in the 18th and early 19th century quite compelling. I felt driven to write a story about this onerous practice and the effect it must have had on young men, and indeed on entire families in that time and place.

Thus, thanks to music, I found myself writing about the last decade of the 19th century and the first few years of the 19th—in other words, the Regency era and the Napoleonic era.

Wikipedia says “The Regency era of British history is commonly applied to the years between c. 1795 and 1837, although the official regency for which it is named only spanned the years 1811 to 1820.”

“Madigan’s Leap” is set in an alternative version of Ireland during this era. It incorporates many aspects of the social, political and geographical elements of Ireland at that time, but I am a fantasy writer, after all, so this is a fantasy tale, and it bends many of the facts to suit the story.

I did my best, nonetheless, to clothe the characters in some of the (hopefully) historically accurate and exquisite costumes of that time. Most people agree, it was a time of exceptionally stylish attire for the military and for the wealthy. Isn’t that one of the many reasons we all love the novels of Jane Austen? 🙂 It is also said that “The uniforms of the Napoleonic Wars were some of the most elaborate and dashing in military history.”

The Churchyard Yarrow

Compliments of the Season!

As mentioned in my last post, Ford Street Publishing is producing a fantasy anthology in March 2024, and my story “The Churchyard Yarrow” is included. The book’s title is “Borderlands: Tales from the Edge — a new anthology.”

Let me tell you something about the background of my short story. It’s an excerpt from a work I’ve recently finished writing. The novel’s title is THE KING’S SHILLING, and it is Book #1 in a new trilogy called MADIGAN’S LEAP.

I began this work some while ago, and it was originally intended to be a short story.

I set it aside for what I thought was a year or two, but when I eventually looked at it again this year, my word processing software informed me that I had typed the first word in 2008. Even back then, the short story was taking on larger dimensions, because I had got as far as the middle of what is now Book #2 before setting it aside.

I recommenced the project, accepted the inevitable reality that it was expanding into three volumes, and completed the trilogy.

Yarrow

Achillea millefolium is commonly known as yarrow. Other common names include old man’s pepper, devil’s nettle, sanguinary, milfoil, soldier’s woundwort, and thousand seal.

You know that when a plant has many common names, it’s one that people find useful.

From Wikipedia: “In antiquity, the plant was known as herba militaris for its use in stanching the flow of blood from wounds. Other names implying its historical use in healing—particularly in the military—include bloodwort, knight’s milfoil, staunchweed, and, from its use in the United States Civil War, soldier’s woundwort.” [Wikipedia: Achillea millefolium]

It’s the “magical” uses of plants that also interests me. Historically, in Ireland, on May Day or the night before, women would place a stocking full of yarrow under their pillow before they went to sleep and recite:

Good morrow, good yarrow, good morrow to thee,

I hope by the yarrow my lover to see;

And that he may be married to me.

The colour of his hair and the clothes he does wear,

And if he be for me may his face be turned to me,

And if he be not, dark and surely may he be,

And his back be turned toward me.[Britten, James (1878). Folk-Lore Record. Vol. 1. Folklore Enterprises, Ltd., Taylor & Francis.]

Ford Street Publishing

I highly recommend Ford Street Publishing when you’re looking for high quality books for children and young adults.

Their mission statement explains that their books explore themes of contemporary relevance. One of their goals is to “provide children and young adults with literary works that explore the significant social issues of our time with intelligence and ingenuity. We see our books as speaking to broad audiences – in Australia and abroad – and not as being ‘issue-bound’ to any marginalised group of which they speak. The quality of our books goes hand-in-hand with building our reputation as a publisher.”

Their mission statement continues: “As well as taking pride in the calibre of our books, we always pay much attention to the design and presentation of our books.

“Our books span beautifully presented picture books for early learners, stimulating titles for the education market, and entertaining and socially conscious books for intermediate readers and young adults. Some of our young adult novels also achieve crossover into adult markets.”

I recommend Ford Street Publishing for their excellence, because director Paul Collins is a friend I’ve known for many years, and because they are publishing a short story of mine in March 2024.

Look out for “Borderlands: Tales from the Edge — a new anthology.” It’s going to be spectacular, with fifty short stories, illustrated by Anne Ryan, and it’s due for release in March 2024.

Isobelle Carmody will write the foreword. Other authors include Bill Condon, David Metzenthen, Kirsty Murray, John Larkin, Justin D’Ath and Simon Higgins.

My contribution is called “The Churchyard Yarrow” and it’s set in a fantasy version of the late 18th century. It is, in fact, a shard of a longer story (another trilogy) – a work in progress.

The Asrai

The Asrai: Wights of the water.

Folklore

In English folklore the asrai are a species of aquatic faery that dwell in freshwater rivers and lakes. (Other aquatic fairies (or “wights”) include sea-dwelling mermaids and nixies, the human-like shapeshifting water spirits of Germanic folklore.)

The asrai are usually depicted as female. They tend to be timid and shy, and may be either quite small, 2–4 ft (0.61–1.22 m) tall, or tall and slender. Being faeries/spirits/wights, they are generally immortal, although they can perish if mistreated.

“Tales from Cheshire and Shropshire (UK) tell of a fisherman who captured an asrai and put it in his boat. It seemed to plead for its freedom in an unknown language, and when the fisherman bound it the touch of its cold wet hands burned his skin like fire, leaving a permanent mark. He covered the asrai with wet weeds, and it continued to protest, its voice getting fainter and fainter. By the time the fisherman reached the shore the asrai had melted away leaving nothing but a puddle of water in the boat, for it will perish if directly exposed too long to the sun. Their inability to survive daylight is similar to that of trolls from Scandinavian folklore.

“Other tales describe the asrai as having green hair and a fishtail instead of legs or may instead have webbed feet. They live for hundreds of years and will come up to the surface of the water once each century to bathe in the moonlight which they use to help them grow. If the asrai ( sees a man she will attempt to lure him with promises of gold and jewels into the deepest part of the lake to drown or simply to trick him. However, she cannot tolerate human coarseness and vulgarity, and this will be enough to frighten her away.”

[“Asrai” – Wikipedia]

Their oldest known appearance in print was the poem “The Asrai” by Robert Williams Buchanan, first published in April 1872, and followed by a sequel, “A Changeling: A Legend of the Moonlight.”

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

“The Asrai” by Robert Williams Buchanan

“Before man grew of the four elements

The Asrai grew of three—fire, water, air—

Not earth,—they were not earthly. That was ere

The opening of the golden eye of day:

The world was silvern,—moonlight mystical

Flooded her silent continents and seas,—

And in green places the pale Asrai walked

To deep and melancholy melody,

Musing, and cast no shades.

“These could not die

As men die: Death came later; pale yet fair,

Pensive yet happy, in the lonely light

The Asrai wander’d, choosing for their homes

All gentle places—valleys mossy deep,

Star-haunted waters, yellow strips of sand

Kissing the sad edge of the shimmering sea,

And porphyry caverns in the gaunt hill-sides,

Frosted with gems and dripping diamond dews

In mossy basins where the water black

Bubbled with wondrous breath. The world was pale,

And these were things of pallor; flowers and scents,

All shining things, came later; later still,

Ambition, with thin hand upon his heart,

Crept out of night and hung the heights of heaven

With lights miraculous; later still, man dug

Out of the caves the thick and golden glue

That knits together the stone ribs of earth.

Nor flowers, nor scents, the pallid Asrai knew,

Nor burning aspiration heavenward,

Nor blind dejection downward under earth

After the things that glitter. Their desires

Shone stationary—gentle love they felt

For one another—in their sunless world

Silent they walked and mused, knowing no guile,

With lives that flow’d within as quietly

As rain-drops dripping with bright measured beat

From mossy cavern-eaves.”

The Trows of Shetland

The trows of Shetland

The trows of Shetland

. . . are among the creatures of folklore that can be glimpsed in the world of the Bitterbynde Trilogy.

Here’s an extract from Book #1 The Ill-Made Mute:

Moonrise came early. Beside Burnt Crag the night orb came up like a copper cauldron and seemed to hang suspended over the hills, at the lip of the horizon. It was then that the music

started up—thin music like the piping of reeds but backed by a rollicking beat made by rattling snares, and the deep thumping thud of a bass drum—music to dance to under the face of the moon.

And, in a clearing not far from the campsite, were those who danced to it—a circle of small gray figures moving awkwardly, without grace.

Thorn laughed softly.

“Come—let us see the henkies and the trows,” he said. “They might bring us joy this night.”

Diarmid demurred, but Imrhien stepped out bravely beside the Dainnan, and they walked together to join the dance.

The quaint, dwarfish folk were silhouetted against the towering shield of the rising moon, black intaglio on burnished copper. Some capered in a bounding, grotesque manner, others

danced exquisitely, with an intricate though uneven step.

From tales told in the Tower, Imrhien knew a little about trows and henkies. They were relatively harmless seelie wights, and their dances did not lure mortals to their deaths in the way of the bloodsucking baobhansith and others. Whether they would take offense at being spied upon was another matter.

The Dainnan did not try to conceal their approach but moved openly across the turf. Tall against the moon’s flare, graceful and lithe as a wild creature, he seemed at that moment

to belong more to the eldritch night than to mortalkind.

The dancers, engrossed in their fun, did not seem to notice the arrival of visitors—the pipers continued to pipe and the drummers to drum. Not as stocky as dwarves, these wights

ranged in height from three to three and a half feet. Their heads were large, as were their hands and feet. Their long noses drooped at the tips, their hair hung lank, stringy, and pallid.

Rather stooped was their posture, and they limped to varying degrees. Imrhien was reminded of club-footed Pod at the Tower—Pod the Henker, he had named himself.

All the wights were clad in gray, rustic garb, the trow-wives with fringed shawls tied around their heads. In contrast with their simple clothing, silver glinted like starlight at their wrists and necks.

The Dainnan turned to Imrhien and swept a bow worthy of a royal courtier.

“Lady, shall you dance with me?”

Further reading:

The Trows of Orkney and Shetland. From the Faery Folklorist blog.

Shetland folklore series: Trows. From the “Shetland with Laurie” blog.

What is a trow? From Orkneyjar.

The trows of Shetland

The trows of Shetland