Here’s a short video that perhaps captures the mystery of the world of Aia, which is the setting for the Bitterbynde Trilogy. It was originally made as a trailer for the audiobook of The Ill-Made Mute. I hope you enjoy it.

Category Archives: Folklore

Golden Hair

Photo by Gustavo Lacerda on Flickr angs school gustavo-lacerda-1

Available under Creative Commons Licence

“Katharine Briggs (8 November 1898 – 15 October 1980) was a British folklorist and writer, who wrote The Anatomy of Puck, the four-volume A Dictionary of British Folk-Tales in the English Language, and various other books on fairies and folklore. From 1969 to 1972, she was president of the Folklore Society, which established an award in her name to commemorate her life and work.” [Wikipedia]

Her book “A Dictionary of Fairies” has been a favourite of mine since childhood. I’ve read it again and again. I’ve loved it so much it started to fall apart and I had it re-bound. The book has since been published under the title, “An Encyclopedia of Fairies“.

Briggs was a passionate, accurate and thorough researcher. She had a PhD with a thesis on Folklore in seventeenth-century literature. She wrote many other books on fairies and folklore, as well as a number of children’s books. “A Dictionary of British Folk-Tales in the English Language: Part A: Folk Narratives (1970)” was re-published in three volumes in 2011 as Folk Tales of Britain, and is described by Philip Pullman in its introduction as the fullest and the most authoritative collection of British folktales that exists.

In 1969 Briggs was awarded the Doctorate in Literature, and made President of the Folklore Society, a post she held until 1972, and which named an award in her honour.

Briggs collected folk tales and fairy tales from people who had learned them, orally, from their forefathers. She found common threads, “types and motifs” within these tales, such as “Mortals as captives in Fairyland”, or “Tree spirits” or “Fairies steal”, or “Mortal not to thank fairy for gifts”. I use many of these motifs in my own work, which is inspired by British and Celtic folklore. One of them is “Golden hair”.

From Katharine Briggs’s “An Encyclopedia of Fairies”:

“GOLDEN HAIR. Some of the FAIRIES were golden-haired, as presumably were the TYLWYTH TEG, or Fair Family, many of the FAIRIES OF MEDIEVAL ROMANCES and the Irish fairies of the TIR NAN OG, but many of them were black-haired and brown-skinned.

“Fair or dark, however, they all set great store by golden hair in mortals. A golden-haired child was in far more danger of being stolen than a dark one. It was often a golden-haired girl who was allured away to be a FAIRY BRIDE, as EILIAN OF GARTH DORWEN was; sometimes, too, the fairies adopted girls of especial beauty, and above all golden-haired, as their special charges; and when they could not protect them they avenged their wrongs.

That said, there appear to be some disadvantages to having golden hair in the Real World!

“Blonde stereotypes are stereotypes of blonde-haired people. Sub-types of this stereotype include the “blonde bombshell” and the “dumb blonde”. Blondes are stereotyped as more desirable, but less intelligent than brunettes. There are many blonde jokes made on these premises. Although chiefly aimed at women, jokes of this style have also been aimed at similar stereotypes associated with men, such as the “dumb jock”, the “surfer dude” and “himbo”.

Wikipedia “Blonde stereotype”

Beautiful golden hair such as that which belongs to the young girl in Gustavo Lacerda’s photo may be the result of albinism, an inherited condition that leads to animals or people (of any race) having very light skin, hair, and eyes. People with albinism are often considered to have a unique beauty. Their hair may be white, auburn or golden.

The Asrai

The Asrai: Wights of the water.

Folklore

In English folklore the asrai are a species of aquatic faery that dwell in freshwater rivers and lakes. (Other aquatic fairies (or “wights”) include sea-dwelling mermaids and nixies, the human-like shapeshifting water spirits of Germanic folklore.)

The asrai are usually depicted as female. They tend to be timid and shy, and may be either quite small, 2–4 ft (0.61–1.22 m) tall, or tall and slender. Being faeries/spirits/wights, they are generally immortal, although they can perish if mistreated.

“Tales from Cheshire and Shropshire (UK) tell of a fisherman who captured an asrai and put it in his boat. It seemed to plead for its freedom in an unknown language, and when the fisherman bound it the touch of its cold wet hands burned his skin like fire, leaving a permanent mark. He covered the asrai with wet weeds, and it continued to protest, its voice getting fainter and fainter. By the time the fisherman reached the shore the asrai had melted away leaving nothing but a puddle of water in the boat, for it will perish if directly exposed too long to the sun. Their inability to survive daylight is similar to that of trolls from Scandinavian folklore.

“Other tales describe the asrai as having green hair and a fishtail instead of legs or may instead have webbed feet. They live for hundreds of years and will come up to the surface of the water once each century to bathe in the moonlight which they use to help them grow. If the asrai ( sees a man she will attempt to lure him with promises of gold and jewels into the deepest part of the lake to drown or simply to trick him. However, she cannot tolerate human coarseness and vulgarity, and this will be enough to frighten her away.”

[“Asrai” – Wikipedia]

Their oldest known appearance in print was the poem “The Asrai” by Robert Williams Buchanan, first published in April 1872, and followed by a sequel, “A Changeling: A Legend of the Moonlight.”

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

“The Asrai” by Robert Williams Buchanan

“Before man grew of the four elements

The Asrai grew of three—fire, water, air—

Not earth,—they were not earthly. That was ere

The opening of the golden eye of day:

The world was silvern,—moonlight mystical

Flooded her silent continents and seas,—

And in green places the pale Asrai walked

To deep and melancholy melody,

Musing, and cast no shades.

“These could not die

As men die: Death came later; pale yet fair,

Pensive yet happy, in the lonely light

The Asrai wander’d, choosing for their homes

All gentle places—valleys mossy deep,

Star-haunted waters, yellow strips of sand

Kissing the sad edge of the shimmering sea,

And porphyry caverns in the gaunt hill-sides,

Frosted with gems and dripping diamond dews

In mossy basins where the water black

Bubbled with wondrous breath. The world was pale,

And these were things of pallor; flowers and scents,

All shining things, came later; later still,

Ambition, with thin hand upon his heart,

Crept out of night and hung the heights of heaven

With lights miraculous; later still, man dug

Out of the caves the thick and golden glue

That knits together the stone ribs of earth.

Nor flowers, nor scents, the pallid Asrai knew,

Nor burning aspiration heavenward,

Nor blind dejection downward under earth

After the things that glitter. Their desires

Shone stationary—gentle love they felt

For one another—in their sunless world

Silent they walked and mused, knowing no guile,

With lives that flow’d within as quietly

As rain-drops dripping with bright measured beat

From mossy cavern-eaves.”

Waterhorses

Waterhorses across the world

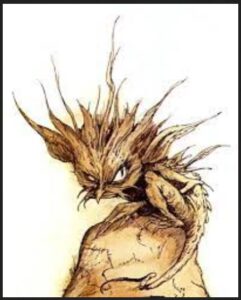

The Each Uisge. Image by Cecilia Dart-Thornton.

Certain folklore themes and motifs cover vast geographical areas. “Waterhorses” can be found in the folklore of England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, as well as Scandinavian countries. Bodies of water such as lakes and rivers are so mysterious, elemental and often dangerous, it’s no wonder so many tales have evolved concerning creatures that might dwell beneath them.

Waterhorses can be benevolent, tricksy (practical jokers) or unseelie (malevolent). They may dwell in fresh water, such as mill ponds or wild forest pools, or in brackish inlets like sea lochs, in the ocean. Some of the waterhorse species are listed below.

Each-uisge

The each-uisge (Scottish Gaelic, literally “water horse”) is a water spirit in Scottish folklore, known as the each-uisce (anglicized as aughisky or ech-ushkya) in Ireland and cabyll-ushtey on the Isle of Man. It usually takes the form of a horse, and is similar to the kelpie but far more vicious.

The folklorist Katharine Briggs called the each-uisge “perhaps the fiercest and most dangerous of all the water-horses”.

Briggs says that the each-uisge is a shape-shifter, disguising itself as a fine horse, pony, a handsome man or an enormous bird. If, while in horse form, anyone mounts it, they are only safe as long as the each-uisge is ridden out of sight of water. However, the merest glimpse or smell of water means the beginning of the end for the rider, for the each-uisge’s skin becomes adhesive and the creature immediately plunges into the deepest part of the water with its victim. After the victim has drowned, the each-uisge tears him apart and devours the entire body except for the liver, which floats to the surface.

In its human form the each uisge is said to appear as a handsome man, who can only be recognised as a magical being by the long green ribbons of water weeds growing in its hair.

Nokken

Waterhorse by Brian Froud

The Norse Waterhorse, the Nokken, is a water demon that lives in rivers and lakes. He is able to transform himself into many shapes, and his purpose is to lure people to their doom.

A Nokken can change into:

-a grey/white horse, and if you ride this horse, you will ride to your death.

– a raft on the water. If you sit down on it, you will float away….to your death.

– a water lily. If you pick this flower, he will come up from the water and drag you down.

– a beautiful young man. If he seduces you, death will be your groom.

The Nokken is known by many other names, including the Nixie, Nixy, Nix, Näcken, Nicor, or Nok. (German: Nixe; Dutch: nikker, nekker; Danish: nøkke; Norwegian Bokmål: nøkk; Nynorsk: nykk; Swedish: näck; Faroese: nykur; Finnish: näkki; Icelandic: nykur; Estonian: näkk; Old English: nicor)

The southern Scandinavian version can transform himself into a horse-like kelpie, and is called a Bäckahästen (the “brook horse”).

Kelpie

Boy on White Horse by Theodore Kittelsen

A kelpie, or water kelpie, is a shape-shifting spirit inhabiting lochs in Scottish folklore.

The kelpie is a powerful and beautiful black horse inhabiting the deep pools of rivers and streams of Scotland, preying on any humans it encounters. It is also able to shape-shift into human-like form.

In some cases, kelpies take their victims into the water, devour them, and throw the entrails to the water’s edge. In its equine form the kelpie is able to extend the length of its back to carry many riders together into the depths; a common theme in the tales is of several children clambering onto the creature’s back while one remains on the shore. Usually a little boy, he then pets the horse but his hand sticks to its neck. In some variations the lad cuts off his fingers or hand to free himself; he survives but the other children are carried off and drowned, with only some of their entrails being found later.

The origins of narratives about the creature are unclear but the practical purpose of keeping children away from dangerous stretches of water and warning young women to be wary of handsome strangers has been noted in secondary literature. [Wikipedia, “Kelpie”]

Ceffyl Dŵr

The Welsh version is called the Ceffyl Dŵr – literally “water horse”.

Nygel, Nigle, Nuggle, or Noggle

A relatively harmless, tricksy waterhorse of Orkney, who can spin his tail like a propeller. The tail is said to be “like the rim of an immense wheel turned up over his back.”

Nygels are supposed to appear near streams of running water, and particularly near water-mills, where, in the night, they might seized and hold fast the water-wheel with their

teeth, until people drove them away by throwing flaming brands at them.

Shoepultie or Shoopiltie ( Shetland Islands)

Shoopilties are as malevolent as kelpies.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

From THE ILL-MADE MUTE:

A white pearl shone like an eye in a hazy sky. The sun was past its zenith, sinking towards a wintry horizon. It cast a pale gleam over the waters of the lake. The entire surface was lightly striated with long ripples, shimmering in silken shades of grey. Through a frayed rent in the clouds, a crescent moon rode like a ghostly canoe, translucent. A flock of birds crossed the sky in a long, trailing V-formation. Their cries threaded down the wind – wild ducks returning home.

Dead trees reached their black and twisted limbs out of the waters, and near the shore, long water-grasses bowed before the breeze, their tips bending to touch their own trembling reflections. Tiny glitters winked in and out across the wavelets. The play of light and shadow masked the realm that lay beneath the lake. Nothing could be seen of the swaying weeds, the landscapes of sand and stone, the dark crevasses, any shapes that might, or might not, move deep under the water.

As the wild ducks passed into the distance, the tranquillity of the lake was interrupted. Faint and first, then louder, yells and laughter could be heard from the eastern shore. A band of Ertishmen was approaching.

Eight of them came striding along, and their long, tangled hair was as red as sunset. They were accompanied by dogs, retrievers wagging feathery tails. Baldrics were slung across the shoulders of the men, quivers were on their backs and longbows in their hands. At the belts of some swung a brace of fowl, tied by the feet. Already they had had a successful day’s hunting. Buoyed by success, their spirits were high. This last foray to the eastern shores of the lake was considered no more than a jaunt – they did not intend to hunt seriously, as was evidenced by the noise they were raising. They chaffed and bantered, teasing one another, sparring as they went along. All of them were young men, hale and strong – indeed, the youngest was only a boy.

“Sciobtha, Padraigh,” laughed the two eldest, slapping him on the back as he ran to keep up, “Ta ocras orm! Tu faighim moran bia!” The looks of the two Maghrain brothers were striking – tall, copper-haired twins in the leather kilts and heavy gold torcs of Finvarnan aristocracy. Their grins were wide and frequent, a flash of white across their brown faces.

“Amharcaim! Amharcaim!” shouted Padraigh suddenly, pointing to the black and leafless alders leaning at the lake’s edge. The men halted and turned their heads.

A shadow moved there. Or was it a shadow?

Gracefully, with arched neck, the stallion came walking out from among the trees. Clean were his lines, and well-moulded; long and lean his legs, finely tapered his frame. He had the build of a champion racehorse in its prime. His coat was sleek and glossy as the water of the lake. . .

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Further reading:

Briggs, Katharine (1976). An Encyclopedia of Fairies, Hobgoblins, Brownies, Boogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books. pp. 115–16. ISBN 0-394-73467-X.

The Spriggans of Cornwall

Spriggans!

Spriggans!

Spriggans are creatures from Cornish faery lore. They’re particularly associated with West Penwith in Cornwall, UK.

These malevolent “unseelie” wights are mentioned in editor Joseph Wright’s 1905 book “The English Dialect Dictionary. Vol. V” and eleven years later in one of my favourite books, Robert Hunt’s “Popular Romances of the West of England”, but the oral storytelling tradition places them much earlier than that.

More recently, in the 21st century, spriggans (or at least the term “spriggans”) seem to have been kidnapped by “The Elder Scrolls”, a series of action role-playing video games. “Spriggan” is also the title of a Japanese manga series (スプリガン).

In the original folklore tradition, “Spriggans were depicted as grotesquely ugly, wizened old men with large childlike heads. They were said to be found at old ruins, cairns, and barrows guarding buried treasure. Although small, they were usually considered to be the ghosts of giants and retained gigantic strength, and in one story collected by Robert Hunt, they showed the ability to swell to enormous size. Hunt associated these spirits with the hillfort known as Trencrom Hill in Cornwall.

“Spriggans were notorious for their unpleasant dispositions, and delighted in working mischief against those who offended them. They raised sudden whirlwinds to terrify travellers, sent storms to blight crops, and sometimes stole away mortal children, leaving their ugly changelings in their place. They were blamed if a house was robbed or a building collapsed, or if cattle were stolen. In one story, an old woman got the better of a band of spriggans by turning her clothing inside-out (turning clothing supposedly being as effective as holy water or iron in repelling fairies) to gain their loot.

“On Christmas Eve, spriggans met for a midnight Mass at the bottom of deep mines, and passersby could hear them singing. However, it was not spriggans but the buccas or knockers who were associated with tin mining, and who played a protective role towards the miners.

“Based on the collections of Robert Hunt and William Bottrell, Katharine Briggs characterized the spriggans as fairy bodyguards. The English Dialect Dictionary (1905) compared them to the trolls of Scandinavia.”

[Source: Wikipedia, “Spriggan”.]

Being a fan of the great folklore collector Katharine Briggs, I too depict spriggans as faerie bodyguards in The Bitterbynde Trilogy.

The Trows of Shetland

The trows of Shetland

The trows of Shetland

. . . are among the creatures of folklore that can be glimpsed in the world of the Bitterbynde Trilogy.

Here’s an extract from Book #1 The Ill-Made Mute:

Moonrise came early. Beside Burnt Crag the night orb came up like a copper cauldron and seemed to hang suspended over the hills, at the lip of the horizon. It was then that the music

started up—thin music like the piping of reeds but backed by a rollicking beat made by rattling snares, and the deep thumping thud of a bass drum—music to dance to under the face of the moon.

And, in a clearing not far from the campsite, were those who danced to it—a circle of small gray figures moving awkwardly, without grace.

Thorn laughed softly.

“Come—let us see the henkies and the trows,” he said. “They might bring us joy this night.”

Diarmid demurred, but Imrhien stepped out bravely beside the Dainnan, and they walked together to join the dance.

The quaint, dwarfish folk were silhouetted against the towering shield of the rising moon, black intaglio on burnished copper. Some capered in a bounding, grotesque manner, others

danced exquisitely, with an intricate though uneven step.

From tales told in the Tower, Imrhien knew a little about trows and henkies. They were relatively harmless seelie wights, and their dances did not lure mortals to their deaths in the way of the bloodsucking baobhansith and others. Whether they would take offense at being spied upon was another matter.

The Dainnan did not try to conceal their approach but moved openly across the turf. Tall against the moon’s flare, graceful and lithe as a wild creature, he seemed at that moment

to belong more to the eldritch night than to mortalkind.

The dancers, engrossed in their fun, did not seem to notice the arrival of visitors—the pipers continued to pipe and the drummers to drum. Not as stocky as dwarves, these wights

ranged in height from three to three and a half feet. Their heads were large, as were their hands and feet. Their long noses drooped at the tips, their hair hung lank, stringy, and pallid.

Rather stooped was their posture, and they limped to varying degrees. Imrhien was reminded of club-footed Pod at the Tower—Pod the Henker, he had named himself.

All the wights were clad in gray, rustic garb, the trow-wives with fringed shawls tied around their heads. In contrast with their simple clothing, silver glinted like starlight at their wrists and necks.

The Dainnan turned to Imrhien and swept a bow worthy of a royal courtier.

“Lady, shall you dance with me?”

Further reading:

The Trows of Orkney and Shetland. From the Faery Folklorist blog.

Shetland folklore series: Trows. From the “Shetland with Laurie” blog.

What is a trow? From Orkneyjar.

Spriggans!

Spriggans! The trows of Shetland

The trows of Shetland