Waterhorses across the world

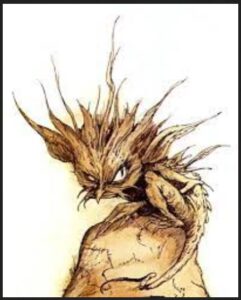

The Each Uisge. Image by Cecilia Dart-Thornton.

Certain folklore themes and motifs cover vast geographical areas. “Waterhorses” can be found in the folklore of England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, as well as Scandinavian countries. Bodies of water such as lakes and rivers are so mysterious, elemental and often dangerous, it’s no wonder so many tales have evolved concerning creatures that might dwell beneath them.

Waterhorses can be benevolent, tricksy (practical jokers) or unseelie (malevolent). They may dwell in fresh water, such as mill ponds or wild forest pools, or in brackish inlets like sea lochs, in the ocean. Some of the waterhorse species are listed below.

Each-uisge

The each-uisge (Scottish Gaelic, literally “water horse”) is a water spirit in Scottish folklore, known as the each-uisce (anglicized as aughisky or ech-ushkya) in Ireland and cabyll-ushtey on the Isle of Man. It usually takes the form of a horse, and is similar to the kelpie but far more vicious.

The folklorist Katharine Briggs called the each-uisge “perhaps the fiercest and most dangerous of all the water-horses”.

Briggs says that the each-uisge is a shape-shifter, disguising itself as a fine horse, pony, a handsome man or an enormous bird. If, while in horse form, anyone mounts it, they are only safe as long as the each-uisge is ridden out of sight of water. However, the merest glimpse or smell of water means the beginning of the end for the rider, for the each-uisge’s skin becomes adhesive and the creature immediately plunges into the deepest part of the water with its victim. After the victim has drowned, the each-uisge tears him apart and devours the entire body except for the liver, which floats to the surface.

In its human form the each uisge is said to appear as a handsome man, who can only be recognised as a magical being by the long green ribbons of water weeds growing in its hair.

Nokken

Waterhorse by Brian Froud

The Norse Waterhorse, the Nokken, is a water demon that lives in rivers and lakes. He is able to transform himself into many shapes, and his purpose is to lure people to their doom.

A Nokken can change into:

-a grey/white horse, and if you ride this horse, you will ride to your death.

– a raft on the water. If you sit down on it, you will float away….to your death.

– a water lily. If you pick this flower, he will come up from the water and drag you down.

– a beautiful young man. If he seduces you, death will be your groom.

The Nokken is known by many other names, including the Nixie, Nixy, Nix, Näcken, Nicor, or Nok. (German: Nixe; Dutch: nikker, nekker; Danish: nøkke; Norwegian Bokmål: nøkk; Nynorsk: nykk; Swedish: näck; Faroese: nykur; Finnish: näkki; Icelandic: nykur; Estonian: näkk; Old English: nicor)

The southern Scandinavian version can transform himself into a horse-like kelpie, and is called a Bäckahästen (the “brook horse”).

Kelpie

Boy on White Horse by Theodore Kittelsen

A kelpie, or water kelpie, is a shape-shifting spirit inhabiting lochs in Scottish folklore.

The kelpie is a powerful and beautiful black horse inhabiting the deep pools of rivers and streams of Scotland, preying on any humans it encounters. It is also able to shape-shift into human-like form.

In some cases, kelpies take their victims into the water, devour them, and throw the entrails to the water’s edge. In its equine form the kelpie is able to extend the length of its back to carry many riders together into the depths; a common theme in the tales is of several children clambering onto the creature’s back while one remains on the shore. Usually a little boy, he then pets the horse but his hand sticks to its neck. In some variations the lad cuts off his fingers or hand to free himself; he survives but the other children are carried off and drowned, with only some of their entrails being found later.

The origins of narratives about the creature are unclear but the practical purpose of keeping children away from dangerous stretches of water and warning young women to be wary of handsome strangers has been noted in secondary literature. [Wikipedia, “Kelpie”]

Ceffyl Dŵr

The Welsh version is called the Ceffyl Dŵr – literally “water horse”.

Nygel, Nigle, Nuggle, or Noggle

A relatively harmless, tricksy waterhorse of Orkney, who can spin his tail like a propeller. The tail is said to be “like the rim of an immense wheel turned up over his back.”

Nygels are supposed to appear near streams of running water, and particularly near water-mills, where, in the night, they might seized and hold fast the water-wheel with their

teeth, until people drove them away by throwing flaming brands at them.

Shoepultie or Shoopiltie ( Shetland Islands)

Shoopilties are as malevolent as kelpies.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

From THE ILL-MADE MUTE:

A white pearl shone like an eye in a hazy sky. The sun was past its zenith, sinking towards a wintry horizon. It cast a pale gleam over the waters of the lake. The entire surface was lightly striated with long ripples, shimmering in silken shades of grey. Through a frayed rent in the clouds, a crescent moon rode like a ghostly canoe, translucent. A flock of birds crossed the sky in a long, trailing V-formation. Their cries threaded down the wind – wild ducks returning home.

Dead trees reached their black and twisted limbs out of the waters, and near the shore, long water-grasses bowed before the breeze, their tips bending to touch their own trembling reflections. Tiny glitters winked in and out across the wavelets. The play of light and shadow masked the realm that lay beneath the lake. Nothing could be seen of the swaying weeds, the landscapes of sand and stone, the dark crevasses, any shapes that might, or might not, move deep under the water.

As the wild ducks passed into the distance, the tranquillity of the lake was interrupted. Faint and first, then louder, yells and laughter could be heard from the eastern shore. A band of Ertishmen was approaching.

Eight of them came striding along, and their long, tangled hair was as red as sunset. They were accompanied by dogs, retrievers wagging feathery tails. Baldrics were slung across the shoulders of the men, quivers were on their backs and longbows in their hands. At the belts of some swung a brace of fowl, tied by the feet. Already they had had a successful day’s hunting. Buoyed by success, their spirits were high. This last foray to the eastern shores of the lake was considered no more than a jaunt – they did not intend to hunt seriously, as was evidenced by the noise they were raising. They chaffed and bantered, teasing one another, sparring as they went along. All of them were young men, hale and strong – indeed, the youngest was only a boy.

“Sciobtha, Padraigh,” laughed the two eldest, slapping him on the back as he ran to keep up, “Ta ocras orm! Tu faighim moran bia!” The looks of the two Maghrain brothers were striking – tall, copper-haired twins in the leather kilts and heavy gold torcs of Finvarnan aristocracy. Their grins were wide and frequent, a flash of white across their brown faces.

“Amharcaim! Amharcaim!” shouted Padraigh suddenly, pointing to the black and leafless alders leaning at the lake’s edge. The men halted and turned their heads.

A shadow moved there. Or was it a shadow?

Gracefully, with arched neck, the stallion came walking out from among the trees. Clean were his lines, and well-moulded; long and lean his legs, finely tapered his frame. He had the build of a champion racehorse in its prime. His coat was sleek and glossy as the water of the lake. . .

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Further reading:

Briggs, Katharine (1976). An Encyclopedia of Fairies, Hobgoblins, Brownies, Boogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books. pp. 115–16. ISBN 0-394-73467-X.

Spriggans!

Spriggans! The Silver Metal Lover

The Silver Metal Lover Alan Lee

Alan Lee