Border reivers.

I was rereading one of my own books the other day, (because it’s being made into an audio-book – hurrah!), and I was reminded of the concept of “dangerous northern dwellers, who are always threatening to surge down south and cause mayhem”.

I started writing THE ILL-MADE MUTE twelve years before it was published, because it took me four years to write each book of the BITTERBYNDE trilogy. In other words, I started around the year 1988. By that stage of my life, the concept of perilous northern raiders was ingrained into my psyche. Which is how they got written into the book.

This is because I was raised on a diet of books that included a great deal of British history, such as the wonderful books of Rosemary Sutcliff and Andre Norton. And throughout British history runs a theme of Dark Forces in the North, threatening the more civilised forces in the south.

Even Mrs Gaskell’s classic NORTH AND SOUTH hints at this. In it, Northerners are typically “hard”, and live in a hellish landscape, while Southerners are soft and live amongst gardens. When I started writing my trilogy it seemed natural to me to invent a world in which trouble was brewing at the northern end. The idea of a wall between north and south also seemed somehow natural, and rather exciting. I’m guessing that’s due to the ghost of Hadrian’s Wall haunting my mind, when I was a child.

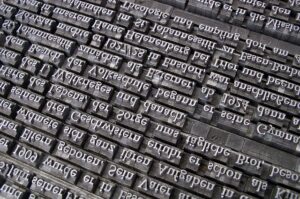

Throughout much of British history, there have been border reivers. They were raiders and outlaws along the Anglo-Scottish border from the 13th to the 16th century, who took advantage of a fraught and explosive border region over those centuries. Their feats have blended into folklore. “There were reiver families and clans on both sides of the border – the English reivers would raid into Scotland and vice versa.” [Wikipedia]

Probably, many of the books I read as a child were written by southerners who might have had a biased impression of the northerners, which is why I ended up with that impression.

Incongruously, my reading left Young Me with the impression that “north is cold”. “Cold north wind” is a phrase that sounds right to my ears, despite the fact that where I live, the north wind in summer comes roaring with the breath of a furnace.

Combined with the Christmas cards of my childhood, that depicted snow and robins, this made for mentally living in two worlds simultaneously. Which is, surprisingly, a boon for a writer.